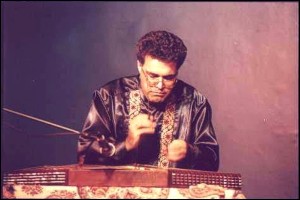

SIAMAK NOORY

The Persian Santurist - Part 1

SIAMAK NOORY

The Persian Santurist - Part 1

Andrián Pertout speaks with Persian santurist Siamak Noory about his musical initiation, and his association with one of Iran's greatest contemporary composers and master santurists, Faramarz Payvar.

Siamak Noory was born in Tehran in 1961, and initiated his musical education at the age of five via Orff instruments (children's instruments designed by Carl Orff [1895-1982] such as the xilophon, metalophon, and vibraphon). Following a seven-year period, he then adopted the Persian santur (a 72-string [or 18 quadruple-stringed] box zither), initially learning the instrument under the guidance of Ms Farzaneh Noshad (a student at the Persian Traditional Music Conservatory in Tehran ). Three years later he is accepted as a student of “one of Iran 's greatest contemporary composers and master santurists,” Faramarz Payvar. For the next eight years Qmars develops his knowledge and understanding of the complete Persian classical music repertoire. As well as this, he synchronically studies Western music – the pianoforte with Taher Djalili (a pianist from the Music Conservatory), and for a year, the bassoon with Khosrow Soltani.

Tell me about your early years in Tehran, and

your initiation into both Persian and Western music.

SN: “I have always been very keen about music,

and did listen to all sorts of music, Persian traditional, Persian pop, Western

classical, and folk music as well. Anyway, music was a big part of my life and

knew that I wanted to become a musician. But I had no opportunity to get to

my goal. There was a library near my house, which was built for children and

teenagers, and I used to go there to play Chess and read books. I also started

to do different courses in all sorts of arts, such as painting, music, film

making, theatre, etcetera. I tried all of them, but something stopped me in

the music course. I felt that I could not live without music, and started to

play Orff instruments until I was eleven years old. Then our leader said that

we had to choose a main instrument for our further education. I really loved

to play the piano, but there wasn't any possibility for me because my family

was poor and nobody could help me to get a piano for me. I was obliged to choose

another instrument, and so I chose the santur by accident. Now I am very proud

that I put my time to play the santur, because it is a unique instrument. There

are not so many people that can play it professionally, and I can express my

feelings via this instrument easily. And people are more interested in the santur,

because they do not know much about it and it is quite new to them.

“Later, I worked hard to save money to buy a piano, and I finally bought

one and started to practice ten hours a day. I was very thirsty about music,

and wanted to play as much as I could to make myself satisfied. I completed

the whole Persian radif in four years, which normally takes between eight to

ten years. I used to listen to Western classical music a lot in those days with

my friend Naser Nazar. We were two close friends, among sixteen music pupils,

that continued our musical life. He is still in Iran and has a private music

school, and we still talk to each other sometimes on the phone. I also owe very

much to my teacher Mohamad Reza Darvishi, who is a great composer and musicologist/ethnomusicologist

in Iran (he has been offered the first prize for his book from Etnomusicological

committee in 2002). He got his Masters in music - educated at Tehran University

– and played the trumpet. Darvishi encouraged me and my friend Naser to

continue our musical life and pushed us to work hard. He helped us a lot, and

we used to borrow tape cassettes from him to listen to. My friend and I were

very poor and didn't even have enough money to eat properly, and Darvishi could

understand our feelings and used to lend us a few tape cassettes weekly. Of

course the music he lent us was only Western classical music, because at that

time we were very keen about this music. When I started to play the santur I

realised that I had a special feeling for Persian art music. This music could

take my mind to the past, to the ancient time of Persia, a great empire. Today

I really love both musics because both of them are art music. These musics are

in my mind all the time, and I am very happy because I happen to know both of

them.”

How did your association with one of Iran's greatest contemporary composers and master santurists, Faramarz Payvar come about?

SN: “I started to play the santur with Miss Farzaneh Noshad. She helped me a lot with the technique, and understanding the tradition. She was studying at the music conservatorium in Tehran. Later on, while I was working at the Radio and Television in Tehran, I met Miss Mina Oftadeh. Mina was a pupil of Payvar, and one day she took me to the Master’s class and introduced me to him. I had always dreamt of studying with Payvar and he had always been my idol as far as santur playing. Oftadeh thought that I had enough capacity, and was ready to work with a great master like Payvar. When I played for the Master for the first time, he was listening carefully and said, 'You are the one that MUST continue studying with me, and I am looking for people like you.' From then on we became very close, and not only for music's sake but also with regards to learning about the tradition.”

Could you describe the relationship between teacher and pupil in Persian art music culture?

SN: “The relationship between a pupil and his teacher in Persian tradition is quite different to Europeans. If you want to become a musician, you have to respect your teacher highly and be with him all the time. This is the tradition which has been taking place for centuries. Your teacher means a lot to you, because he is the unique person who has inherited the written and oral tradition. It is the responsibility of a pupil to respect his/her teacher and obey him in order to learn the tradition. Your teacher must trust you a hundred percent transfer all his knowledge. He must find it out with time, that you are really talented and have a heart of gold. You, as a true pupil, must show him and prove to him that you really want to learn the tradition. It takes time to be close to the masters. Payvar also did not like to take women on as pupils, because he thought that after many years of teaching them they would finally marry and build a family, and their career would finish. That is true because most women in Iran do not continue their music life after marriage. Unfortunately the religious atmosphere does not let them continue their career. Even for men it is very difficult to be a professional musician. It is shame for a family to have a professional musician in their family, and they always want their children to become a medical doctor.”

'Pardis - Persian Solo Santur' distributed by Siamak Noory. For further information contact Siamak Noory on (0431) 638 358. Email: sianoory@hotmail.com

ANDRIÁN PERTOUT

'Mixdown' Monthly ~ Issue #97, May 4, 2002

BEAT MAGAZINE PTY LTD

All rights reserved. All text,

graphics and sound files on this page are copyrighted.

Unauthorized reproduction and

copying of this page is prohibited by law. Copyright © 2002 by Andrián Pertout.

![]()

SIAMAK NOORY

The Persian Santurist - Part 2

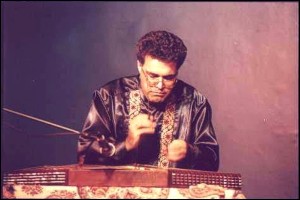

Andrián Pertout speaks with Persian santurist Siamak Noory about the history of his instrument, and his performances in and around Tehran in the early 80s.

The Iranian santur is an integral part of the traditional orchestra, sharing the lute repertoire of the tar and setar. It is also utilized in the motrebi ‘entertainment music' genre, but folk styles are excluded. An article by Jean During, Scheherazade Q. Hassan, and Alastair Dick describes the santur's constructing thus: “The santur consists of a trapeziform case made of walnut wood, approximately 90 cm wide at the broad end, 35 cm wide at the narrow end and 6 cm deep. The sides form an angle of 45 degrees to the wider end. The strings are fixed to hitch-pins along the left-hand side and wound round metal wrest-pins on the right by means of which they are tuned with a tuning-key. Each quadruple set of strings rests on a movable bridge of hardwood (kharak). These bridges are aligned almost parallel with the sides of the case. The right-hand rank corresponds to the bass strings and that on the left to the treble strings. In the centre of the santur the low-pitched strings on the right cross the high-pitched strings on the left.” Adding to this, the instrument features three courses of strings (the bass strings made of brass, while the treble ones, steel), with a total of 72 strings or 18 groups of strings, capable of producing 27 different pitches, and is played “by striking the strings with two hammers (mezrab) held in three fingers of each hand.”

What is the history of the instrument that you play, the Persian santur?

SN: “Santur and the name of Payvar have become synonymous in Iran. Whenever the name of santur appears in a book or in an article, the name of Payvar joins the article as well. And a brief description of this instrument is central to an understanding of Payvar's contribution to Iranian music. Today dulcimer-type instruments such as the santur are almost an international instrument, being played from the USA in the West, to China in the East. The santur plays an important role in both folk and classical music in many countries. It also takes an important part in the Dance & Folk Festival (Tanz & Folk Fest) at Rudolstadt in Germany, which is held every year. In 1996, Faramarz Payvar was invited to play at that festival, which I attended. There I met many different santur players from different parts of the world such as Iran, the USA, Hungary, China, Germany, Switzerland, Greece, Austria, Rumania, Russia, Iraq, Turkey, and India. Dulcimer-type instruments have different names in different countries, such as Das Hackbrett (Germany), cimbalom, or zimbalum (Hungary), santir (all Arab countries), sandori (Greece), Yangchin (China), and psaltery, or dulcimer (English countries). Surprisingly, I noticed that the santur-type was very popular around the world, and was made in different sizes and played in different ways.

“And the history of the santur goes back to ancient times, and can be traced to a millennium BC. In some Babylonian (1600-911 BC) and neo-Assyrian (911-612 BC) iconographical documents we can find a horizontal harp, which is related to today's santur (dulcimer-type). Also, in the Old Testament the name of santir appears among other instruments which were in use at that time. Mehdi Setayeshgar - an Iranian santur player and researcher - in his book “Santur's Speciality in Iranian Music” states that: 'The earliest documentation of the existence of santur was found in the archaeologist's excavation site which belonged to Babylon and Assyrian (669 BC) in the South-west of Iran. This documentation shows similarity to today's santur, but unlike today's players, the santur player of that time used to hang the instrument on his neck with the help of a rope.' In Europe the instrument was, and still is, in use in the field of folk music, and has changed form to suit current musical needs. Nevertheless, in many European countries the santur-type or dulcimer is still widely played on different occasions. The cimbalom is also used in symphony and chamber orchestras. Some famous composers like Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) have composed pieces that include cimbalom, and skilled players like Aladar Racz and Toni Irdache have played them.”

Did you perform in and around Tehran in those days? If so, what type of occasions were they?

SN: “As I mentioned before, I started to learn music in special libraries, which were made for children and teenagers. These libraries belonged to the government and called 'Kanoon-e Parvareshe Fekriye Koodakan va Nojavanan'. Children from the age of five or six could go there and learn to read, and attend different courses. Music and painting courses were the most popular courses, among others. The Orff method which came from Germany, was very good and attracted children. Still my friend Mr. Nazar teaches this method not only to children but to adults as well. I can remember having a concert for Carl Orff and his assistant in Tehran in 1978. We were twenty kids who were chosen from different libraries in Tehran, and worked very hard for about two months to prepare some pieces to play for Orff and his company. After the concert he was so astonished to hear very technical pieces on an instrument that had been invented for children. He could not believe his eyes. We played some Persian music, which was arranged for Orff instruments, and also some classical Western music. For example, some Hungarian dances by Brahms, the last part of symphony number nine by Beethoven, the first part of symphony number forty by Mozart, and some other pieces. Orff was very surprise to see us playing such beautiful pieces on his instruments and decided to take us all to Germany to study music professionally. Everything was arranged, and the government was very happy to be sending twenty of us to Germany to become professional musicians. But unfortunately a few months later, Islamic revolution happened in Iran and everything was ruined by the new regime. The Shah was obliged to escape from Iran, music conservatories were shut, and music became illegal and counted a big sin to be played and to be listened.

“But I played with our Orff group until twelve years old. I then started to play the santur and progressed very fast. At the age of fifteen I had already started to give concerts as a professional musician. Ostad (Professor or Master) Payvar had a programme for his pupils to play monthly in a private concert that he arranged himself. Ostad also asked me to play every month in those private concerts and I had to prepare new pieces for these occasions. Payvar inherited this tradition from Vaziri and also put on ‘free concerts’ in his advertisements to help people attend the concerts. He wanted to encourage people to go to such concerts, and tried showing them that music is not only illegal but also and is a beautiful phenomena in this cosmos.”

'Pardis - Persian Solo Santur' distributed by Siamak Noory. For further information contact Siamak Noory on (0431) 638 358. Email: sianoory@hotmail.com

ANDRIÁN PERTOUT

'Mixdown' Monthly ~ Issue #98, June 5, 2002

BEAT MAGAZINE PTY LTD

All rights reserved. All text,

graphics and sound files on this page are copyrighted.

Unauthorized reproduction and

copying of this page is prohibited by law. Copyright © 2002 by Andrián Pertout.

![]()

SIAMAK NOORY

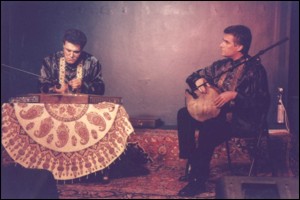

The Persian Santurist – Part 3

Andrián Pertout speaks with Persian santurist Siamak Noory about the Iranian music scene before the Islamic revolution, and the general change of attitude towards music and musicians post 1979.

In 1979, the Islamic revolution in Iran bestowed the study of music with an illegal status, consequently bringing about the premature closure of the Music Conservatory. “Because of the Islamic revolution in 1979, which caused an undemocratic situation, more than 3,000,000 Iranians became obliged to escape from the country. Of these three million nearly 60,000 came to Sweden during the 1980s. More than 1,000,000 people fled to USA and the rest mostly went to Germany, France, and other European countries,” explains Siamak. After the fact, for his own ‘anti-establishment’ beliefs in artistic freedom, he too becomes a victim of the ongoing institutionalised persecution. He recalls the events of 1981 leading to his arrest and two-year imprisonment:

“In the winter of 1981 I was playing piano in my apartment. I used to play at least eight hours a day, which did not please the Moslem neighbours. Suddenly, I heard some noises from downstairs. I waited in my room, knowing that there were people downstairs talking about me. They came up and without knocking rushed into my room. One of them used to be my close friend – before the revolution – who felt very envious of me with regards to my music. He was now working for the Islamic Army, which was created after the revolution. They told me that it was illegal to play an instrument or listen to music. They took away my grand piano, all my records and books, arrested me and put me in jail for nearly two years. I do not want to discuss what I saw and what they did to me, but instead what I want to say is that freedom is the most important thing in our human life and that I tangibly experienced how political persecution became a negative factor for Persian Art, especially music...”

What were some of your other activities within the Iranian music scene before the Islamic revolution of 1979?

SN: “I was also working on Radio & Television in Tehran, in the children section. I was working there with Mr Vanko Naidanoff, a Bulgarian musician and we made some concerts there, and I used to sing in the choir. In the concerts we used to use different instruments; a mixture of Orff and the standard instruments, like trombone, bassoon, clarinet, violin, piano, and some other instruments. I also used to also play live in a theatre in Tehran. Some of my friends worked at the Ferdowsi Theatre – a middle size theatre hall in the middle of the city of Tehran – and I used to play the santur and sometimes Orff instruments in their theatre. The music for the theatre was composed by other musicians, and I only played it at their live show. I used to play alone and some times together with other musicians. I can tell you that I started such a wonderful musical life in Tehran and it is a pity that it did not last long. It now seems like a dream to me. I was growing fast in my musical life and working hard to get to my goal. I fought not only with my religious family who were against music, but also with a society that thought that a musician was worse than a prostitute. So you can imagine how difficult it was for me to get my goal in that society, and still I am fighting for it. I am now trying to produce CDs, continue my further studies, doing PhD at Monash under Professor Margaret Kartomi and Dr Reis Flora, write articles and books, etcetera.”

How did the general attitude towards music and musicians change post 1979?

SN: ““I believe strongly that music is a great part of human life and that no one can prevent or stop people playing instrument or listening to the music. Could you imagine life without music? Everything in this cosmos is based on melody and rhythm, such as birds singing, movement of water, animals jumping and running, the sea, a tree growing, and etcetera. But in Iran, as soon as the Islamic regime took power announced that according to the Quran and Islam music is illegal. They started to shut down all music schools, conservatoriums, universities and music institutes. No one could even listen to music in their privacy. There was no music on radio and television and the only ‘music’ that was allowed to be listened to were some marches and religious hymns (Quran recital) that called for music. They needed marches for war; to excite people (the war with Iraq). But people then started to learn music privately, because they could feel that life without music was empty and very boring.

“Today in Iran, in most families someone plays an instrument, and this is very good for Iranian society because music helps them express their feelings about all the pressures that comes from the regime. Music for me was and still is the ‘only’ way to express my feelings such as sadness, happiness, anger, etcetera. Today music became extremely popular in Iran, which is quite opposite to the time of the Shah. At that time music was of course free to be played and listened to, but people were not so interested in participating in groups or learning to play an instrument. The commercial music, which we call it ‘chip music’ or ‘motrebi’, was taking over, and the Shah was trying to Westernize Iran with these sort os music. He invited many famous groups from Europe and spend millions of dollars to make Iranian to be familiar to the Western culture. There was only Western hip-hop and roc music on the Radio & Television all the time. Today the situation is different, and healthy music (not commercial Western and Persian classical music) is growing fast. The political situation has also changed today, and with the new President, Mohamad Khatami, people can breathe a little more compared to Khomeini’s time. The regime knows that people want democracy and freedom, and that is why they give people a little more freedom, because they want to stay on power. But we are still far from being a real democracy. Music schools, institutes, universities and conservatoriums are privately doing their duty to the society, but everything is private. Today people are not allowed to drink alcohol, but they do make and produce their own wines and spirits at home privately. So everything is private today.”

‘Pardis – Persian Solo Santur’ and ‘Sé Rox Dar Segah’ distributed by Siamak Noory. For further information contact Siamak Noory on (0431) 638 358. Email: sianoory@hotmail.com

ANDRIÁN PERTOUT

'Mixdown' Monthly ~ Issue #101, September 4, 2002

BEAT MAGAZINE PTY LTD

All rights reserved. All text,

graphics and sound files on this page are copyrighted.

Unauthorized reproduction and

copying of this page is prohibited by law. Copyright © 2002 by Andrián Pertout.

![]()

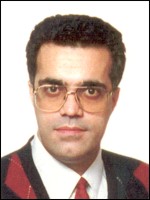

SIAMAK NOORY

The Persian Santurist – Part 4

Andrián Pertout speaks with Persian santurist Siamak Noory about his eventual arrest and imprisonment in 1981 (when the Islamic revolution in Iran bestowed the study of music with an illegal status), and his ultimate escape from Iran in 1986.

Siamak ultimately escaped from Iran in 1986 (during the Iran-Iraq war of the eighties), arriving in Turkey as a refugee, to then temporarily settle in Belgium where he studied the piano at the Music Academy in Antwerp with Hedvig Vanvarenberg before establishing a permanent base in Sweden in 1989. Here he studied the piano for two years at the Birkagårdens Folkhögskolan in Stockholm with Stella Tchaikowsky, and went on to graduate from the University of Göteborg with a Bachelor of Science in Musicology. Since 2001, Siamak has been living in Melbourne, Australia. He recently completed a Masters degree (Ethnomusicology) at the University of Melbourne.

The events that followed ultimately lead to your eventual arrest and imprisonment in 1981. How did you cope in prison?

SN: “The period that I spent in prison will never get out of my mind, and is unforgettable, but to think about those black days and nights makes me strong, and always encourages me to be more ambitious on my way and Iranian musical culture. The regime tortured me hard in the prison – I’ve still got the signs on my back – because I was musician? Why did I play the piano and the santur? Why did I become a musician? They wanted me to tell them my friends' names, who were also musicians, but they failed. Before that I had heard many times that music was illegal in Islam, but it had not been a serious problem until facing the Islamic army (Sepah Pasdaran), who took me to jail. Prison was a nightmare for me. To be in a small room with nearly eighty prisoners – all political prisoners – is not an easy task. I was living with people who were awaiting their execution in the following day or week. There, in the prison I faced lots of brave people, who were raised against the regime and were put in the jail. I have learnt a lot from those people. I was also active to teach those innocent people something about music and encouraged them to listen to the music history with its glorious in the past and in present time. I was trying to show them that music is not hobby and not for entertainment. I talked about Beethoven, his music and his personality. Beethoven’s spirit has been always with me, and I have learnt a lot from this great master, how to think freely and how to appreciate freedom. Beethoven is one of my Gods and I always admired him that he had changed the title of his third symphony, which had been dedicated to Napoleon Bonapart in the first place, but when Napoleon became a dictator, Beethoven changed his mind and renamed it Eroica.”

How did you eventually escape from Iran and become an exile in Europe?

SN: “To be in exile is very difficult because you never feel at home. To escape from Iran especially in wartime was a huge risk. It was so dangerous and difficult to trust smugglers, because the only thing, which is important to a smuggler is money. They haven’t got any feelings for you and are not concerned about your life. I, with five friends of mine – two of them from the prison time – decided to leave the country. Life became very difficult, and especially for me as a musician. It was impossible to live in Iran after revolution because music counted as illegal and so there was no musical activity in the society. Poor people could not breathe, and make any objections against the regime, because people have been told that the country was in a state of war (war between Iran and Iraq). Anyway, we paid lots of money to the smugglers to take us to Turkey. You may ask, from where did I get the money? I sold my books and other property, and also received money from my teacher Ostad Payvar and my family. Otherwise I could not have offered it. Smugglers took us from a city near the border of Iran and Turkey (Rezaiyeh) to Turkey. And life in Turkey was very dangerous for Iranians, because in the past there had been many wars between Ottomans and Persians, and so we were not safe there at all. Anyway, in Turkey we stuck it out in a very bad situation. Millions of Iranians were obliged to escape from Iran and go to Europe via Turkey, and smugglers became millionaires from the money that Iranians paid them. Unfortunately the Turkish police and army caught many Iranians and handed them over to the Iranian Islamic army (Sepah Pasdaran) in the border. They were receiving a lot of money from the Iranian government for each person delivered to them. Turkish police imprisoned many Iranians in Ankara and Istanbul. They savagely raped poor young Iranian girls, and even boys who were escaping from their country to settle in peace. I really cannot describe everything, but for more information about prisoners in Turkey I strongly suggest for everybody to see a film called ‘Midnight Express’, which was made by an American imprisoned in Turkey, who finally succeeded in escaping.

“I stayed in Turkey for more than a year. I had no money to eat, and was living with eight people in a two-room apartment in Istanbul. The smugglers then sent me to Belgium, which was also a problem for me. Belgium is a very small country with ten million inhabitants, and people in Belgium are generally against foreigners. Refugees have serious problems there. Unfortunately, today racism in European countries grows rapidly and people in Europe probably do not know WHY a refugee escapes from his/her own country. What cause them to flee to other countries? I really want encourage people in the West to think about this case because, they have to realise that nobody wants to leave their native country/home and leave everything behind.

“Anyway, I settled in Antwerp, which is a city situated in the north. The city was beautiful, and I found a few nice people there. Nice people are everywhere of course, and if I talk about the difficulties in European countries I just talk in a general sense. The laws in Belgium say that refugees are not allowed to work or study. I do not know about today’s situation, but this law was very much against my future at the time in 1986. I had not escaped from Iran to come to Europe and sit around at home taking money from the government, and doing nothing. I had come to do my further studies in music. So, I started going to the music academy to study the piano without telling anybody. I had to be very careful because if the government found out, it may have meant being deported to Iran. Anyway, while I was waiting for the result of my candidature as a refugee, I studied music in Mortsel music academy in Antwerp for free and thanks to the head of the school Mr. Cuypers who kindly helped me in all way he could. After three years I moved to Sweden, because some of my friends told me that I could achieve my goal in Sweden.

“Sweden is a very beautiful country, and social life, even for refugees was very good until 1994-1995. After 1995 the political and economic situation changed. But when I initially moved to Sweden in 1989, the situation for refugees was pretty good, and all refugees got help to study or work. I called the music academy in Stockholm (Birkagårdens Folkhögskolan) from a refugee camp, and told them that I was a musician from Iran and wanted to study there. They invited me to Stockholm and conducted a test. After the test I was accepted, and after a few months began my studies there. At that time I only spoke English, and so the staff in the music academy helped me to learn the Swedish language. I was studying from 8am to 4pm at the music academy, and from 6pm to 9pm I attended evening classes to learn Swedish. This situation continued for two years. I finished my studies and took my papers to the music conservatorium in Göteborg, where I studied musicology for three years. After getting my bachelor from Göteborg University I planned to do my Masters and PhD, but problems started. As I mentioned before, after 1995, the social, political and economic situation had changed a lot, and racism had risen. And not only in Scandinavian countries, but throughout Europe. The staff in the musicological department did not want me to go further, a professor saying to me, “It is better for you to find another job, and do something else with your life.” His words were like a knife going into my heart. They simply did not want foreigners in the musicological institute. I did not know what to do, but fortunately I received my Swedish citizenship and my friends encouraged me to go abroad to do further studies. I applied for my Masters at UCLA in America, Auckland University in New Zealand, and Melbourne University in Australia. I was accepted in all of them, but USA was very expensive for me and did not know anything about New Zealand, so I chose Melbourne. I can tell you that Australia is the best country, and especially Melbourne, which is a multicultural city. I love the weather, and people are very nice. During my three semesters studying in Melbourne I have made many friends, but while living in Sweden for more than 12 years I can say that I have not got even one Swedish friend. It is very difficult for refugees living in Europe, and so I admire Australia for their concern about different cultural groups. After my studies I plan to go to Iran and help my people, because it is a musician’s duty to go back and preserve their musical culture.””

‘Pardis – Persian Solo Santur’ and ‘Sé Rox Dar Segah’ distributed by Siamak Noory. For further information contact Siamak Noory on (0431) 638 358. Email: sianoory@hotmail.com

ANDRIÁN PERTOUT

'Mixdown' Monthly ~ Issue #103, November 6, 2002

BEAT MAGAZINE PTY LTD

All rights reserved. All text,

graphics and sound files on this page are copyrighted.

Unauthorized reproduction and

copying of this page is prohibited by law. Copyright © 2002 by Andrián

Pertout.

![]()